Ricky McCormick’s remains were well on their way toward fertilizing the soil when investigators arrived to the scene in late June 1999. Filthy Lee blue jeans and a stained white T-shirt clung to his scrawny five-foot-six-inch frame. Although it had been just three days since he disappeared, the flesh on his outstretched hands was already rotted to the point that his fingertips, just below the top knuckles, had fallen off and lay next to him in the weeds.

Ricky McCormick’s remains were well on their way toward fertilizing the soil when investigators arrived to the scene in late June 1999. Filthy Lee blue jeans and a stained white T-shirt clung to his scrawny five-foot-six-inch frame. Although it had been just three days since he disappeared, the flesh on his outstretched hands was already rotted to the point that his fingertips, just below the top knuckles, had fallen off and lay next to him in the weeds.

How his corpse ended up facedown in this cornfield in rural St. Charles County — twenty miles from where he worked and lived in downtown St. Louis — was anyone’s guess. But the desolate sliver of land between the Mississippi and Missouri rivers has been a criminal dumping ground for years.

In 1995 authorities discovered the bullet-ridden body of an alleged prostitute in an abandoned house along the same stretch of U.S. Route 67. Two years after McCormick’s death, state road crews mowing grass some 300 yards away from where he lay found the nude bodies of two more women.

The notes seem to display elements of secret languages and simplified phonetic spellings. For example, “MLSE” could be code for “miles.”

Advanced decomposition made an autopsy of McCormick difficult. Following a thorough examination of the 72 pounds of bones and flesh that survived exposure to the elements, pathologists with the St. Charles County Medical Examiner’s Office ultimately ruled McCormick’s cause of death “undetermined.” Yet police suspected foul play.

Homicide detectives searched the 41-year-old victim’s pockets for clues and interviewed his relatives, girlfriend and others who knew him. Soon leads began to run dry, and a stack of other cases piled up on investigators’ desks. Before long McCormick appeared to join the ranks of countless other poor, indigent men whose short lives ended under suspicious circumstances only to be forgotten.

Twelve years passed, and then everything changed.

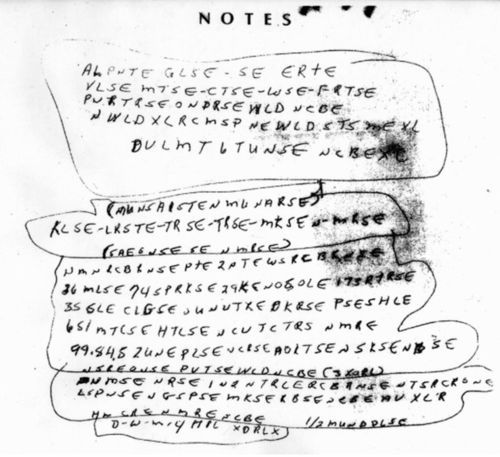

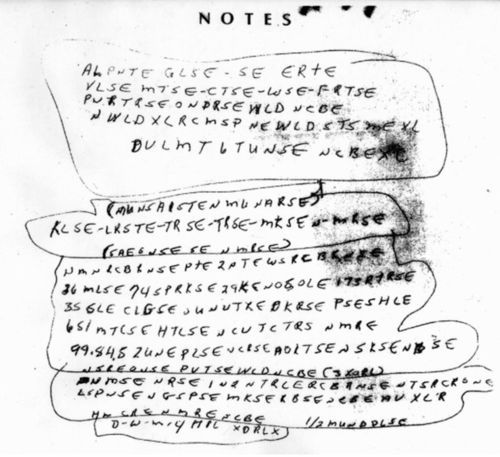

In March 2011, FBI officials made a rare and remarkable revelation, seemingly out of the blue. Dan Olson, chief of the bureau’s Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit (CRRU) in Quantico, Virginia, disclosed for the first time the existence of two pages of handwritten encrypted notes found stuffed in a pocket of McCormick’s jeans. Unable to decipher the tangle of letters and numbers, the FBI released copies to the public with a plea for assistance to hardcore puzzle solvers and wannabe sleuths alike.

It turns out McCormick’s riddle, allegedly written by a man who could hardly write his own name, has stumped the world’s foremost code breakers. They remain so baffled, in fact, that McCormick’s notes now rank third on the CRRU’s list of top unsolved cases, behind only an unbroken cipher authored by the self-proclaimed Zodiac killer in 1969 and a secret threat letter written to an undisclosed public agency about 25 years ago.

FBI code breakers typically unlock the meanings of ciphers they receive in a matter of hours. McCormick’s notes have eluded Dan Olson for more than a decade. Although he has since been promoted to lead the bureau’s cryptanalysis unit, Olson was a forensic analyst when the McCormick codes first made their way east to Quantico in late 2001. He’s been puzzling over them ever since.

Olson projects a clinical approach to his job: disciplined, methodical, emotionally detached. When the McCormick codes originally hit his desk, Olson attacked them as he always does, counting characters and looking for patterns. He attempted to break them down manually with graph paper and a pencil. He dissected the strings of letters and numbers on whiteboards amid the acrid whiff of dry-erase markers. He employed computers with state-of-the-art software to perform statistical analyses. Olson worked on the codes for two solid weeks.

He got nowhere.

He brought in other analysts to take a look and brainstorm ideas and consulted experts for clues. He compared the letters and numbers in the notes to every street address in St. Louis and vetted them against maps from across the country, but no hits rose to a level beyond coincidence.

“It doesn’t happen often that we have an unsolved cipher of this length and significance,” Olson says. “The characters are not random. There are many E’s, for example, that could be used as a spacer. There are many characteristics that suggest it could be solved, many patterns. The problem is we don’t know why it is not solvable.”

Cracking a code takes four steps. First one must determine the language used, in this case, English. Then the system used — a cipher in which letters are transposed or substituted for something else, for example, or a code in which a letter such as “R” represents a person or place, or perhaps even a secret language such as a version of pig Latin. After

that one must reconstruct the key that explains how the code maker changed the letters of the message, such as by shifting every character three letters to the right in the alphabet. Finally, one can apply the key and transcribe the intended text.

“We cannot get past step two,” Olson says of the McCormick case.

Some have suggested the notes are meaningless, the random scribblings of a man who by all accounts was functionally illiterate and demonstrated a low IQ. Olson is quick to argue otherwise. He is convinced the codes could contain leads about where McCormick was or with whom he met in the last hours before his corpse was abandoned to rot along with his secrets.

“This means something,” Olson says. “We look at a lot of things that are gibberish, arbitrary strikes on a keyboard. This is not that case.”

The McCormick notes eventually moved to the back burner. But a few years ago, with some new staff and capabilities in the FBI laboratory, Olson decided it was time to revisit the case and bring in some fresh eyes. Approximately fifteen of the twenty analysts on staff applied their experience and techniques to the codes. Still nothing worked, putting McCormick’s handiwork in rare company. The FBI examines hundreds of suspected codes each year. After weeding out those that are nonsense from the codes the bureau categorizes as solvable, only about 1 percent go unbroken, Olson says.

In September 2009, Olson’s frustrated team looked outside for help. They presented the McCormick puzzle to a room of about 25 amateur code breakers gathered in Niagara Falls, Ontario, for the annual convention of the American Cryptogram Association. The challenge generated interest, but association members have been unable to make any breakthroughs.

The FBI has been stumped for a decade but insists the writings have meaning.

Despite investing hundreds of hours to decipher the mystery over nearly a decade, the FBI’s elite CRRU — the same unit that cracked the codes of Nazi spies during World War II — remained foiled by the apparent craftsmanship of a high school dropout.

Olson’s rare, and some would say humbling, decision to appeal to the masses last year for help garnered immediate attention. Local newspapers and TV stations in Missouri and Illinois ran with the update. So did news organizations from as far away as New Zealand, Germany and Ghana.

The deluge that followed prompted the FBI to establish a special Web page just to handle the more than 7,000 public comments and theories that have poured in so far. Respondents have suggested the encrypted notes could mask information about everything from vehicle identification numbers, gambling books and drug-dealing transactions to addresses and directions, mental-health episodes or medications. The list goes on and on. Sifting through them all has prompted seven or eight conversations about potential leads between Olson’s team and local investigators, he says. But no arrests or significant developments in the case have emerged. The secrets buried in the codes remain as mysterious as the events that precipitated McCormick’s death.

Ricky McCormick always stood out as different from his peers. His mother, Frankie Sparks, describes him as “retarded.” His cousin Charles McCormick, who shared a brotherly relationship with Ricky for most of his life, says Ricky would often talk “like he was in another world” and suspects Ricky might have suffered from schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

“Ricky went to see a psychiatrist, and he said Ricky had a brick wall in his mind,” remembers Gloria McCormick, an aunt better known as “Cookie” in whom Ricky often confided. “He said Ricky refused to break that wall. He didn’t like the life of living poor and had an active imagination.”

It’s unclear whether McCormick ever received formal treatment for mental illness, but family members recall Ricky’s penchant for concocting tall tales and his displays of unusual behavior. As a boy he spent so much time at recess standing off by himself that his mother would receive calls from school administrators asking if anything was wrong.

Teachers shuffled McCormick along from grade to grade, but he could hardly read or write when he dropped out of St. Louis’ former Martin Luther King High School on North Kingshighway.

McCormick subsisted on occasional odd jobs — floor mopper, dishwasher, busboy, service-station attendant — and disability checks he collected due to chronic heart problems. He preferred the graveyard shift and developed a reputation as a night owl, heading out the door at dusk and dragging himself home at dawn.

“I called him a vampire,” Gloria McCormick says. “He slept all day, and then at night he rises.”

As a teenager and later as an adult, he frequently hitched a ride or caught a bus to distance himself from the street toughs who dealt drugs and picked fights outside his now-bulldozed home near the present-day intersection of Lindell Boulevard and North Sarah Street.

Eventually Ricky found trouble himself. In November 1992, St. Louis police arrested the 34-year-old McCormick for having fathered two children with a girl younger than fourteen years old. McCormick had been sleeping with the girl since she was eleven, according to court files, which protected the girl’s identity. McCormick’s mother and aunt knew the girl simply by her nickname, Pretty Baby.

While awaiting trial on the first-degree sexual-abuse charge, McCormick’s public defender noted she had reasonable cause to believe McCormick was “suffering from some mental disease or defect” and requested that the judge order a mental-health exam. Dr. Michael Armour, a local psychologist, evaluated McCormick at the former St. Louis State Hospital. Following Armour’s report and a hearing, however, the court certified McCormick was fit for trial. Six weeks later, on September 1, 1993, McCormick pleaded guilty to the crime. State inmate 503506 would spend thirteen months behind bars in the Farmington Correctional Center before being sent home a year early on conditional release.

McCormick’s relationship with Pretty Baby reflected an obvious lapse of good judgment. It wouldn’t be his last.

McCormick may have been regarded as something of a simpleton who, despite some street smarts and his criminal record, was generally naïve to the world. The same cannot be said for the men who ran the Amoco gas station at 1401 Chouteau Avenue south of downtown St. Louis where he worked.

Fawaz M. Hamdan, the original owner of the business, killed his neighbor with a butcher knife during a front-yard argument in May 1994. He later died in Missouri’s Potosi Correctional Center while serving a life sentence for second-degree murder.

Juma Hamdallah, a Palestinian immigrant who until 2002 used the name David Radigan, took over as president of the business. Juma employed his brother Baha “Bob” Hamdallah. Despite their familial ties, the two have had a rocky relationship. In August 1999, less than two months after McCormick’s death, police from Maryland Heights investigated an incident in which Juma allegedly shot Baha. Baha Hamdallah survived and filed no charges, but, according to police records, detectives looking into the shooting gathered information allegedly linking Baha “to black gang members in St. Louis City and narcotics use” and noted “Baha is reported to be violent and in possession of several weapons which include handguns and knives.”

Indeed, among the Hamdallah brothers (another, Jameil Hamdallah, is a registered sex offender), Baha appears to be the most volatile. Police reports and witness statements spanning several years illustrate repeated episodes of violence that seemed to accompany him wherever he went.

Shortly after moving to St. Louis in 1997 from Cleveland, Ohio, then 22-year-old Baha Hamdallah was cruising the streets of St. Louis in a blue Mazda Protegé when a police detective saw him pull up alongside a man named Tarrence Clark, lean out his car window and fire a shot at him with a .38-caliber revolver, according to the police report of the incident and witness statements. Clark escaped unharmed. Baha was arrested but never prosecuted.

Nine months later, on the evening of March 4, 1998, Baha Hamdallah was visiting one of his older brothers, Bahjat Hamdallah, at his job at the Family Market, a small corner grocery store in the Tower Grove East neighborhood. They got into an argument, and Baha allegedly grabbed a gun and opened fire on Bahjat from across the street. A bullet tore into the left side of Bahjat’s abdomen and knocked him to the ground. Baha jumped into his car and sped off.

The eyewitness reports, including that of the manager who knew Baha from frequent visits to the store, were consistent in the police report. But a bloodied Bahjat, either out of fear or a remaining shred of fraternal loyalty, told police he had never seen his assailant before and described him as a goateed Hispanic man rather than his five-foot-ten, 225-pound Middle Eastern brother.

Six days later Baha Hamdallah turned himself in and was arrested on a felony charge of first-degree assault, but Bahjat told police he did not wish to prosecute. State court files show no record of the case.

Later the same month, while working at the family’s Amoco station, Baha Hamdallah was arrested again, this time on a felony charge of second-degree assault, for allegedly beating a man named Elroe Carr with a rusty hammer. Baha allegedly threatened to kill Carr, described by family and acquaintances as a sometimes-homeless drug addict, if he didn’t get off the property. Baha told police, “I just figured I’d take care of this myself,” according to the incident report.

On August 7, 1998, two weeks before Carr’s case against Baha Hamdallah was slated to go to court, Carr was gunned down just blocks from the Amoco station on a residential street in the neighboring housing project. The pending assault charges against Baha died that night with Carr.

Carr’s murder remains unsolved, and police made no arrests. But confidential informants told police Carr was killed “at the behest of Baha Hamdallah,” according to St. Louis police reports obtained through a public-records request.

There would be more violence to come.

Minutes before sunrise on June 15, 1999, about two weeks before his death, Ricky McCormick walked up to the counter at the Greyhound bus terminal downtown and purchased a one-way ticket to Orlando. It would turn out to be the last of at least two brief trips to Florida he made that year.

It’s not clear whom McCormick met during his stay in Room 280 at the Econo Lodge in Orlando. But phone records show he or his girlfriend, Sandra Jones, made a flurry of calls to several people in central Florida a couple of weeks ahead of his arrival. Jones and McCormick exchanged a similar barrage of short phone calls during the two days McCormick spent in Orlando, and he made at least one call to the St. Louis gas station where he worked.

Jones would later tell police she suspected McCormick went to Florida to pick up marijuana. According to a sheriff’s department investigative report, Jones’ explanation went like this:

McCormick would accept offers to pick up and deliver packages for money. He made trips to Florida before and on several occasions brought marijuana into the apartment he shared with Jones in the Clinton-Peabody housing project south of downtown. The drugs would usually be sealed in zip-lock bags rolled together into bundles the size of baseballs. McCormick told Jones he was holding the stashes of weed for Baha Hamdallah, the police report states.

McCormick never liked to talk about his excursions to Orlando, but he seemed different when he got back that last time, Jones told police. He seemed scared.

Indeed, McCormick’s already unsettled lifestyle seemed to become more erratic after he came back, as if he sensed trouble around the corner but didn’t know where to turn. McCormick used much of his time during his last days to seek out medical care or, perhaps more accurately, a safe place to stay.

Around three o’clock the afternoon of June 22, 1999, McCormick walked alone into Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s emergency room complaining of chest pains and shortness of breath. This was nothing new. McCormick had a history of ER visits and had suffered from asthma and chest pains since childhood. He told his doctors he didn’t abuse drugs or alcohol, a statement friends and family back up. It didn’t help, however, that he smoked at least a pack of cigarettes a day since he was about ten years old and drank coffee by the gallon. By his own estimate, he told his doctors he downed more than twenty caffeinated beverages a day.

Doctors ruled out a heart attack but admitted McCormick for observation and kept him there for two days. Ricky left the hospital on June 24 with orders to return for follow-up visits in the coming week. He would never make it to those appointments.

McCormick took a bus to his aunt Gloria’s apartment after leaving Barnes-Jewish and visited with her for about an hour. Her home had always been a sanctuary for him, and he maintained a closer relationship with Gloria than with his own mother, who lived just around the corner.

“Everybody needs someone to talk to now and then,” Gloria says. “Ricky would come visit and talk with me.”

But he revealed little this time, chatting just a bit before getting up to leave. It was late afternoon, and Ricky waved off offers to drive him wherever he needed to go. Gloria’s last image of Ricky is him walking down the street.

Around 5 p.m. the next day, June 25, McCormick entered the emergency room at Forest Park Hospital, less than two miles from Barnes-Jewish. This time he complained that he was having trouble breathing following an afternoon of mowing grass. Doctors diagnosed his wheezing as another asthma flare-up. He was not admitted, however, and was officially released at 5:50 p.m. It’s not clear when he actually left the hospital. Gloria says she heard McCormick spent that night in the waiting room before leaving the next morning.

Jones told police that she talked with McCormick on the phone at about 11:30 a.m. on June 26. He told her he was out of the hospital and was on his way to the Amoco to get a bite to eat. At least one gas-station employee told police he last saw McCormick there the next day, on June 27.

McCormick left the gas station with at most hours left to live; medical examiners determined he was definitely dead the same day.

Looking back, Gloria McCormick suspects Ricky’s hospital visits were attempts to find a hideout where he could lay low. Sitting at an open window in her same apartment, Gloria’s voice softens between tugs on her Salem 100’s cigarettes. “Maybe he knew he got into something that put his life on the line,” she says. “He knew he could have stayed here. But maybe he didn’t want to put my life on the line.”

When McCormick’s corpse turned up, his girlfriend Jones’ thoughts turned to Baha “Bob” Hamdallah. After McCormick returned from his trip south, Jones said she suspected Ricky might have done something wrong in Orlando. If anyone was going to hurt McCormick, she told investigators, it would probably be Bob Hamdallah.

On December 23, 1999, detective Jana Walters of the St. Charles County Sheriff’s Department received a call from Sgt. Ed Kuehner of the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department’s homicide division. He had information to share about Ricky McCormick’s death and wanted to arrange an inter-agency meeting.

Nine investigators gathered on the fourth floor of St. Louis’ police headquarters six days later. In addition to Walters and her partner, detective Michael Yarbrough, Kuehner’s gathering included members of St. Louis’ homicide and narcotics divisions, investigators with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and a special agent from the FBI.

Walters and Yarbrough learned St. Louis police were investigating a man named Gregory Lamar Knox, a major drug dealer who operated in and around the housing complex where McCormick had lived, as a suspect in several homicides, including “at least two murder-for-hire schemes.” According to police records, a confidential informant also told police that Knox was responsible for the murder of a black man who worked at the gas station on Chouteau Avenue and whose body was dumped near West Alton. St. Louis police had also linked the Hamdallahs with alleged “criminal activity and the possible association with Gregory Knox.”

The St. Charles detectives came away from the meeting wanting to know more about the role Knox and the Hamdallahs may have played in McCormick’s death. Within weeks they began conducting stakeouts of the Hamdallahs’ gas station and the homes of several of its owners and employees.

No arrests ever materialized. Yarbrough says that despite ongoing suspicions, detectives never could substantiate claims from informants suggesting a connection between the Hamdallahs and Knox or prove either was responsible for McCormick’s death.

Still, both Knox and Baha Hamdallah found their way to prison, at least for a time.

Knox was arrested on July 25, 2000, and pleaded guilty in January 2001 to charges of possession with intent to distribute crack cocaine and carrying a firearm during and in relation to a drug-trafficking crime. A March 2001 HUD report to Congress noted Knox “was a suspect in at least four homicides that occurred in 1998 and 1999 in the LaSalle Park Homes and Clinton-Peabody public housing developments (in St. Louis). He was also the number one supplier of narcotics to LaSalle Park Homes.” Knox is currently serving his sentence at the Federal Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky, and is scheduled to be released in November 2013.

On October 13, 2000, Baha Hamdallah was managing another store, Charlie’s Food Market in Madison, Illinois, when he got into an argument with a customer named Robert Steptoe. Different versions of events were later presented in court, but ultimately a jury convicted Hamdallah of first-degree murder after he shot Steptoe in the face with a 9-mm Glock pistol outside the store. In September 2002 a Madison County judge sentenced Hamdallah to 38 years in prison for killing Steptoe.

Nearly four years later, however, in May 2006, an Illinois appellate court ruled Hamdallah’s lawyer erred by not calling a gunshot-residue expert to testify in person in the shooting case. The appellate court granted a retrial. In the second go-round, the jury bought Hamdallah’s claims of self-defense and his version of events in which the gun went off while he and Steptoe were struggling for control of the pistol. On May 15, 2008, Hamdallah walked out of court a free man.

Attempts to contact Baha and Juma Hamdallah for this story were unsuccessful. Brother Bahjat Hamdallah says Juma now lives in the Philippines and that Baha has married and relocated back to the Cleveland area in his attempt to start over following his Illinois murder trial.

Gregory Knox, responding by e-mail from prison to questions about McCormick and allegations he was involved in McCormick’s murder, wrote: “At this moment this is all new information to me, and I have no information that could help your case.”

With little left to go on, investigators now believe that the codes found on Ricky McCormick may offer the best hope to explain how his corpse ended up in that isolated cornfield so many years ago. The FBI’s Olson is convinced an answer to the codes is out there, though it will not appear out of thin air.

“Can it be solved? Yes, I am absolutely confident,” Olson says. “But you can’t just will it.”

Today the field in West Alton offers no hint of its murderous history. No marker or makeshift memorial stands in the place where McCormick’s body was found. The cycle of seasons erased long ago what little impression he left behind.

A few miles south, no headstone identifies McCormick’s final resting place at Laurel Hill Memorial Gardens. If not for an entry in the cemetery’s log book, one would never know his bones are buried beneath the grass designated as Space #2 in lot 11D. Here and there other graves are decorated with red silk flowers and plastic green wreaths, but not McCormick’s. There is no sign anyone has ever visited his anonymous plot.

Back in St. Louis, McCormick’s family members say they have never heard from police about the Hamdallahs, Knox or other details of the investigation into Ricky’s death. They never heard about the encrypted notes found in his pocket until the local evening news broadcast a report on the codes.

“They told us the only thing in his pockets was the emergency-room ticket,” McCormick’s mother, Frankie Sparks, says. “Now, twelve years later, they come back with this chicken-scratch shit.”

Contradicting the FBI’s statements to the media, family members say they never knew of Ricky to write in code. They say they only told investigators he sometimes jotted down nonsense he called writing, and they seriously question McCormick’s capacity to craft the notes found in his pockets.

“The only thing he could write was his name,” Sparks says. “He didn’t write in no code.” Charles McCormick recalls Ricky “couldn’t spell anything, just scribble.”

Don Olson stands by his assessment, however.

“I have every confidence that Ricky wrote the notes,” Olson says. “They are done in more of a format of something written to oneself than something written to someone else.” As an example, he points to circles drawn around some segments of code that suggest a to-do list where items are marked as tasks are completed.

Elonka Dunin, an expert amateur cryptographer who has consulted novelist Dan Brown of The Lost Symbol and The Da Vinci Code fame, agrees the McCormick notes appear to be personal. They might be a message from one person to another but do not look as if intended, as with some other famous ciphers, to be challenges to a broader audience, she says. Dunin, a computer-game developer who happens to live a short distance from where McCormick’s body was found, has spent tens of hours during the past year analyzing his notes. Like Olson, she suspected McCormick might have authored them for his own private consumption. Upon learning more about McCormick’s illiteracy and personal background, however, she has second thoughts. “I don’t think McCormick wrote these notes,” she says. “Perhaps he was a courier.”

Olson insists the only reason he decided to make the notes public was to see if somebody would recognize the code or provide new information that could help decipher it.

“Sometimes tips generate a seed that generates an ultimate break,” Olson says. “The codes were released in the hope that someone would see this and suggest ideas. We can become tunnel-visioned. We know a little bit about this case, and sometimes that puts us at a disadvantage.”

At St. Charles County Sheriff’s Department headquarters, detective Yarbrough peers through eyeglasses over a salt-and-pepper mustache. A career cop since 1979, he has seen his share of murders, frauds and other crimes. Few have generated as much exasperation as the McCormick case.

Unincorporated St. Charles County has only seen about five unsolved murders since the 1960s, Yarbrough says. The McCormick investigation remains an unfinished job, an unmet challenge and a professional frustration. He remains unsure whether he will ever know McCormick’s true fate and be able put the mystery surrounding Ricky’s death to rest.

“I still have the same feeling that things don’t add up,” Yarbrough says. “It’s kind of like Humpty Dumpty. All the pieces are there, but how do you put them back together?”